From Stokely to Kwame: The Revolutionary Journey of a Black Power Prophet

By Charles Zackary King

Changing Trends and Times | America in Black and White

In the story of Black liberation, few names echo with as much fire and clarity as Stokely Carmichael, later known as Kwame Ture. His life was a masterclass in transformation: from immigrant child to civil rights warrior, from SNCC chairman to global Pan-Africanist. His journey was not just political, it was spiritual, cultural, and unapologetically Black.

Origins: From Trinidad to the Bronx

Born June 29, 1941, in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael immigrated to Harlem at age 11 to reunite with his parents. Raised by his grandmother and aunts, he arrived in the U.S. with sharp intellect and sharper instincts. He later attended the prestigious Bronx High School of Science, where he began questioning the racial and social structures around him.

Awakening at Howard University

Carmichael enrolled at Howard University in 1960, studying philosophy and absorbing the teachings of professors like Sterling Brown and Toni Morrison. But it was outside the classroom, in the streets and churches of the South, that his activism took root. He joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and became a Freedom Rider, risking his life to desegregate interstate travel.

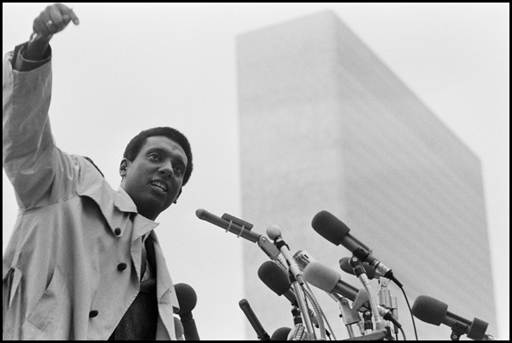

Black Power Rises

By 1966, Carmichael had become chairman of SNCC, succeeding John Lewis. That same year, during a march in Mississippi, he delivered the rallying cry that would define a generation:

“What we want is Black Power.”

This slogan wasn’t just rhetoric, it was a demand for self-determination, racial pride, and political autonomy. Carmichael’s stance marked a shift from integrationist strategies to radical resistance, challenging both white supremacy and liberal complacency.

What Mattered Most: Liberation Over Assimilation

For Carmichael, the Civil Rights fight was never just about access, it was about ownership. He believed that integration, as framed by white society, often meant assimilation into systems that were fundamentally anti-Black. What mattered most to him was:

- Black control over Black communities—from schools and housing to policing and economics.

- Political independence—building all-Black political organizations like the Lowndes County Freedom Organization.

- Economic justice—shaking the foundations of exploitation and demanding reparative systems.

- Cultural pride—rejecting the notion that whiteness was the standard and embracing African heritage unapologetically.

- Global solidarity—connecting the Black struggle in America to liberation movements in Africa, the Caribbean, and beyond.

He once wrote:

“For racism to die, a totally different America must be born.”

This wasn’t a call for reform, it was a call for revolution.

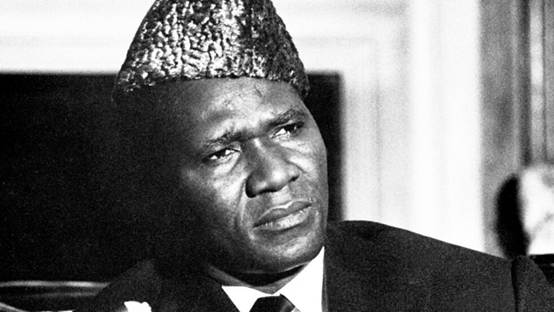

The Name Change: Kwame Ture

In 1969, Carmichael left the U.S. and settled in Guinea, West Africa, alongside his then-wife, South African singer Miriam Makeba. There, he adopted the name Kwame Ture—a tribute to Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and Sékou Touré of Guinea, two titans of Pan-Africanism.

The name change was more than symbolic. It marked a rebirth—a rejection of colonial identity and an embrace of African unity, revolutionary socialism, and global Black consciousness.

Building Pan-African Futures

In Guinea, Ture co-founded the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party (A-APRP), advocating for a united Africa free from imperialism. He traveled extensively, speaking in Cuba, Ghana, and across Europe, always centering the plight of oppressed peoples and the power of collective liberation.

Final Years and Enduring Legacy

Kwame Ture died of prostate cancer on November 15, 1998, in Conakry, Guinea, at age 57. But his voice still reverberates, in classrooms, protests, podcasts, and policy debates. His writings, including Stokely Speaks and Ready for Revolution, remain essential texts for understanding Black resistance and global solidarity.

Why Kwame Ture Still Matters

In today’s climate of racial reckoning and global unrest, Ture’s life offers a roadmap. He taught us that identity is political, that liberation is global, and that Black Power is not a moment, it’s a movement. His transformation from Stokely to Kwame wasn’t just personal, it was prophetic.